My

first article in a glossy mag! (Mine's on the lower half of the page.) OK, it's the CERN Courier, not the New Yorker. But still...

The Long Summer: How Climate Changed Civilization

by Brian Fagan

1816 was widely known as the year without a summer. A massive volcanic eruption in Java, one of the biggest since the last great ice age 20 000 years ago, cast a pall over the Earth. Temperatures plummeted and storms battered crops. Across the world in Geneva, the cold weather kept Mary Shelley indoors, where she entertained her husband and a friend with the now-classic story Frankenstein, a cautionary tale of the dangers of science.

Anthropologist Brian Fagan's The Long Summer is a cautionary tale, too. Modern agriculture and technology help buffer much of humanity from short-term climate shifts, such as the odd drought or flood, volcanic eruption or ocean-current shift. (The summer of 1816 seems to have been merely an inconvenience for the Shelleys.) But, Fagan argues, this buffer is illusory. We are actually more vulnerable than ever to long-term climate change. Fagan's book takes the long view, covering the migrations and development of human societies over the past 20 000 years. He shows how human societies have risen to great heights when the climate was cooperative - but also suffered spectacular crashes when the climate shifted. Archaeologists have long known about these ups and downs of civilization, but many make sense only in the light of relatively recent data on the history of climate change.

From cores from glaciers, lake beds, and the ocean, combined with studies of tree rings and pockets of preserved pollen grains, climatologists have assembled a remarkably detailed record of the climate since the last ice age. Fagan focuses on the picture these records paint, while piecing together a parallel narrative of human societies from the much more scant written records and artefacts people left behind, which give a sense of their lifestyles and movements.

In shifting from mobile to settled life, from diets based on a wide variety of plants and animals to those reliant on a few staples, populations have soared. But in going through this process, which Fagan calls "trading up", people exchanged flexibility and mobility for some measure of stability and prosperity.

But what will happen if there is another major climate shift? Atlantic ocean currents warm Europe, but a few thousand years ago those currents probably shut down when North American glaciers melted, plunging Europe into a mini ice age. Humanity has flourished through the past 15 000 years, a rare stretch of warm, stable climate that Fagan calls the "long summer". Today we do not have the options open to our ancient forebears of shifting back to herder or hunter-gatherer lifestyles. But another major climate change is bound to come, and no doubt sooner rather than later because of human-influenced climate change. When it does, humanity will face tougher decisions and greater chaos than ever before. This book is an attempt to get people thinking about it now.

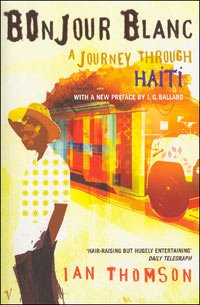

Bonjour Blanc: A Journey Through Haiti

Bonjour Blanc: A Journey Through Haiti Watching the English: The Hidden Roots of English Behavior

Watching the English: The Hidden Roots of English Behavior